Imagine a math class where a group of students become so invested in what they are learning that they purchase their own textbook, meet outside of class to study it, and push themselves far beyond the assigned material. They pursue it not for extra credit or a grade, but out of genuine interest. In most classrooms, that level of intrinsic motivation is nearly unheard of.

Yet in the music wing at York High School, it is becoming increasingly common.

The shift emerges in practice rooms and hallways, in living rooms, and in any space where students can gather with their instruments and a shared sense of purpose. This year, that purpose has taken on a more visible form through the 100 Gig Challenge, a collective effort by York’s student-led chamber ensembles to complete 100 community performances across Elmhurst and the surrounding area.

For those unfamiliar with the term, a “gig” is simply a performance. In this context, it means any small group of students playing music in a public setting: a nursing home lounge, a library atrium, an elementary school music room, a hospital lobby, a church gathering space, or anywhere an organization welcomes them. The groups are small, usually three to six students, and the performances are informal but meaningful. The challenge is straightforward on paper: if the total number of these community performances reaches 100 by the end of the year, York’s chamber musicians will have achieved their goal. But while the number provides structure, the spirit of the challenge lies in everything that happens along the way.

The current total sits around 25, but the significance of the challenge reaches far beyond the number itself.

The idea traces back nearly 17 years, to a small group of students who performed at a local nursing home and witnessed firsthand the emotional response their music could evoke. Residents brightened. A room came alive. Students felt the impact of their playing in a way that went well beyond the walls of their classroom. Their teacher, Michael Pavlik, watched as the students connected immediately to a purpose larger than themselves. The experience revealed something essential: when students understand that their music matters to others, their engagement deepens.

What began as one meaningful visit gradually grew into a culture. Year after year, more students formed their own groups, more community organizations extended invitations, and more performances unfolded across the city. Along the way, Pavlik and fellow band director William Ernst worked together to support the growing program, helping chamber groups find the resources, structure, and encouragement needed to thrive.

Under the direction of orchestra teacher Julie Spring, York’s orchestra students have joined the 100 Gig Challenge this year, bringing an even wider range of instruments and ensembles into the effort. Their participation has further strengthened the culture of collaboration and community engagement across the entire music department.

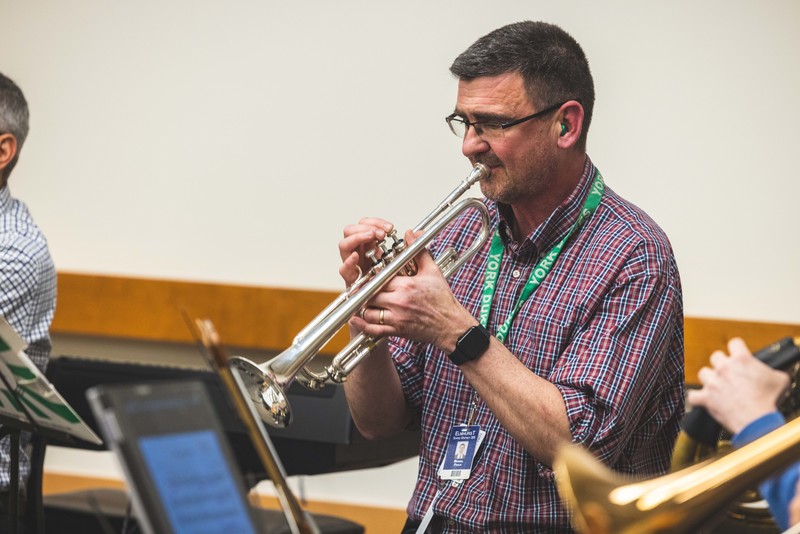

Today, more than 20 ensembles participate. Woodwind quintets, brass choirs, percussion groups, mixed-instrument ensembles, and first-year musicians who are learning what it means to collaborate all take part. During regular school periods, students are given designated time to rehearse in their chamber groups as part of the curriculum, but many also choose to meet before school, after school, or in one another’s homes. Ownership of the process rests almost entirely with the students.

That autonomy encourages creativity. During the Elmhurst Public Library Chamber of Music Concert this fall, students filled the space with a mix of classical works and contemporary arrangements. One ensemble, a student-created polka group, performed a polka-style version of “Sweet Child of Mine,” complete with coordinated outfits and playful instrumentation. It was an illustration of what happens when students are given the freedom to design performances that reflect their personalities and ambitions.

As the culture continued to evolve, groups began scheduling their own gigs, rehearsing independently, and even buying their own music so they could curate a personal library of pieces unique to them. Pavlik gradually stepped back, confident that students would rise to the level of responsibility they had claimed.

This sense of self-direction lies at the heart of the 100 Gig Challenge. Students choose their ensembles. They select their repertoire. They determine how to present themselves and how hard to push one another. They learn to depend on their peers, to hold each other accountable, and to recognize that a group succeeds only when every member is fully invested.

Working for something larger than oneself is woven into the fabric of the challenge. Students rehearse not because they must, but because others are counting on them. They perform not for an evaluation, but to share something meaningful with people who may need it. That dynamic changes everything.

Performances in community settings provide what Pavlik describes as a Goldilocks effect: the perfect balance of urgency and comfort. The performances carry enough weight to motivate students to prepare, but not so much pressure that mistakes feel catastrophic. In that space between the two, trust takes root. Students experience vulnerability, reliance, and interdependence in ways that cannot be replicated in a traditional rehearsal.

Inside small ensembles, each part carries significance. A missed entrance is noticeable. A well-placed cue can bring a group back together. Students learn to communicate with glances, breath, and body language. They make real-time adjustments without waiting for an adult to intervene. Leadership emerges not through assignment, but through necessity.

Those skills extend directly into the full ensemble. Students return with sharper listening, a heightened sensitivity to balance and phrasing, and a clearer sense of how their individual line fits within a larger musical framework. Rehearsals become more efficient, not because the teacher demands it, but because students have learned how to listen, respond, and collaborate at a deeper level.

Equally important is what the challenge avoids. There are no grades tied to the performances. No competitive rankings. No trophies waiting at the end. The motivation is internal. It arises from the group itself and from the community members who benefit from hearing them play. Students practice because they want to honor one another, because they want to make a room sound better, and because they feel the value of what they are offering.

By the time the final performance arrives, the accomplishment will not be defined by reaching 100 gigs. The true achievement will be the growth, the teamwork, and the sense of identity that developed along the way. Students will not only have learned to play music. They will have learned what it means to contribute to something larger than themselves.

And for that reason, the real impact of the 100 Gig Challenge is something that numbers cannot fully capture. It is something that must be felt.